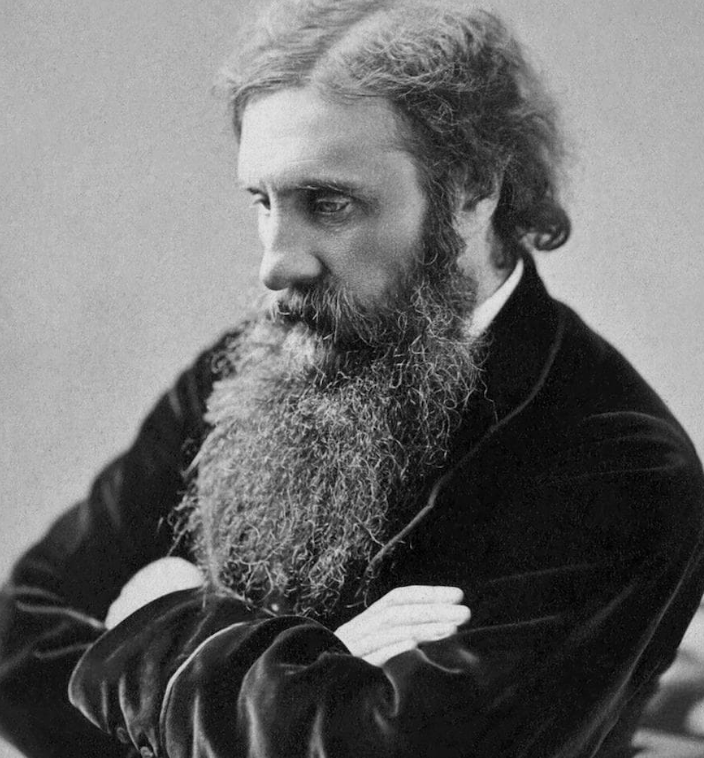

GEORGE MACDONALD

Professor. Poet. Author. Influencer.

“NOBILITY OF THOUGHT IS NOTHING WITHOUT NOBILITY OF DEED.”

The Man and the Impact

George MacDonald (1824–1905) is often remembered as “C.S. Lewis’s master,” a writer whose fantasy and “baptized” imagination deeply shaped the Inklings, the literary discussion group which existed in the early 1930s to the late 1940s, based at the University of Oxford, and whose members included C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Lewis called him his “spiritual father,” and many Anglicans know MacDonald only through that lens. He was a friend to Mark Twain, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Walt Whitman, and mentor to Lewis Carroll. Yet MacDonald was not simply a maker of fairy tales; he was a professor and poet who used story to confront the social wounds of Victorian Britain through a profoundly Christ‑centered, kingdom vision.

Born in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, into a modest Scottish family, MacDonald knew Calvinist rigor and economic insecurity well. His father and grandmother were known for taking in the struggling and orphaned; hospitality to the poor was part of his earliest formation. Illness, frequent moves, and precarious work left him no stranger to the anxieties he later gives his fictional servants, farm laborers, and urban poor.

Ordained in the Congregational Church and later worshiping within the Church of England, MacDonald’s preaching and writing circled constantly around one central conviction: God is like Christ, and Christ shows us the Father’s heart. He reacted strongly against images of God as primarily a legal judge whose goal is to damn and destroy. He argued that God’s justice is love at work—a purifying, patient, fatherly love that will not rest.

For MacDonald, salvation offers a powerful healing force, that we can be freed from selfishness and fear, and be taught to love God and neighbor in concrete ways. Judgment is “consuming fire” that burns away all that is false and destructive. A faith that does not move toward the poor, the sick, the shamed, is, in his view, a wounded or distorted faith.

This vision grows out of his reading of Scripture. Again and again he returns to Isaiah 58, Matthew 25, and James. Isaiah’s call to “share your bread with the hungry” and “bring the homeless poor into your house,” Jesus’ identification with “the least of these,” and James’s insistence that faith without works is dead—these were not marginal texts for him. They sit near the center of Christian obedience. For MacDonald, Jesus saves souls and is re‑making human relationships and calling His people into humble, costly service.

Why, then, did he write novels and fairy tales rather than systematic theology? Because he believed story could reach the heart as well as the head. Lewis and Tolkien called George MacDonald the great mythopoeic writer. Today “mythopoeic” is often taken to mean “epic fantasy,” but for the Inklings it meant something far deeper: a story that not only crosses times and cultures but carries intrinsic power to change its hearers. For Lewis and Tolkien, the Gospel is the supreme mythopoeic tale—not because everyone who hears it is transformed, but because there is something in the story itself that is capable of transformation. MacDonald set out, quite consciously, to write that kind of story, without ever using the word “mythopoeic.”

MacDonald grew up in a world thick with narrative—biblical stories, Scottish folklore, family tales, ballads, and the wider literary tradition—and became convinced that story is one of God’s primary instruments for shaping hearts. Christ himself, after all, answers moral and social questions with parables rather than abstract arguments. MacDonald therefore wrote in many genres—realist novels, children’s tales, and fantasy—not simply to entertain but to form readers’ affections and perceptions. His fiction grew out of a coherent vision of God and of human life, and that vision drives his attention to social issues, poverty, and “the least of these.”

Respectable Christians might nod through a sermon on poverty and remain unchanged; but a story could slip past their defenses. In books like Wilfrid Cumbermede, Sir Gibbie, and The Marquis of Lossie, MacDonald places readers alongside children in poverty, women who have been shamed, embattled service industry workers, and individuals with disabilities who are held in a communal fabric of care. The test of his “good” characters is almost always their ability to “see” and respond to those who aren’t celebrated or even noticed by mainstream society. This is why his engagement with the social issues of Victorian Britain is never mere “issue fiction.” Again and again he forces readers to re‑imagine who is truly noble, who bears Christ’s likeness, and what a Christ‑shaped community might look like. In doing so, he joins that “cloud of stories” through which the great Story continues to remake hearts, homes, and parishes.

One example described by Kristin Jeffrey Johnson, a MacDonald scholar, is that of individuals with disabilities. She highlights that in all of MacDonald’s novels, those with mental or physical impairment are seen as a blessing and a part of the fabric of society. The only person who falls into that category who is not a positive force for the community is a man who has no community. Jeffrey Johnson explains, “I think that’s very intentional. MacDonald is showing that, yes, you can have somebody with disabilities who isn’t safe. But then the question is, why is this person not safe? It’s because this person does not have community.” MacDonald is intentionally painting a beautiful, challenging, and sometimes untidy picture of a biblical, Jesus-centered, and counter-cultural kingdom of God.

Writing into a world spun by the Industrial Revolution, MacDonald’s fiction became a kind of moral laboratory, playing out scenarios that his readers were likely missing in their daily lives. His audience was largely the educated and churchgoing classes—the very people with power to effect change for those lost and neglected in the gears of economic progress.

George MacDonald’s influence and impact is vast– across generations, sectors, and continents. Florence Nightingale copied long passages of his novels, carried them to Crimea, and replaced the heroine’s name with her own to strengthen her courage, vocation, and understanding of God’s mercy in suffering. Lillias Trotter said reading MacDonald at thirteen “completely change[d] her life”; she repeatedly transcribed and quoted him, and her last recorded words were his. Octavia Hill appeared in his fiction as a model reformer, which helped popularize her vision of dignified housing and green space; the MacDonald family partnered with her in inner‑city ministry. MacDonald’s stories shaped Madeleine L’Engle’s integrative, imaginative theology, and the Trinitarian, grace‑centered theology of James Houston and James Torrance. In his own day he rivaled Dickens in sales, filled halls in North America, and helped ordinary readers grasp God as a loving Father.

Jeffrey Johnson sheds light on a classic many of us love, explaining how Oswald Chamber’s wife, compiling My Utmost for His Highest, includes segments of text by George MacDonald. Jeffrey Johnson observes, “This means millions of evangelicals have been spiritually formed by MacDonald without knowing it.”

For Anglicans today, MacDonald gives us a vision of what a fully orbed gospel looks like; in which the Father’s goodness compels attention to “the least of these;” and in which imagination is a powerful formational force of spiritual and social renewal. Christians have always done this work. George MacDonald, during the Victorian era, joins in the myriad of voices in church history and today who point us to Jesus’ light, shaping and re-shaping all of creation.

C.S. Lewis on George MacDonald

-

“I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master; indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it."

“I dare not say GMD is never in error; but to speak plainly I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself.”

-

“My own debt to [GMD's Unspoken Sermons] is almost as great as one man can owe to another: and nearly all serious inquirers to whom I have introduced it acknowledge that it has given them great help – sometimes indispensable help toward the very acceptance of the Christian faith.”

Later in life, when writing to a friend about important teachers of faith, Lewis references people like St Augustine, Athanasius, and Hooker, and then proceeds to explain that for himself, it is to George MacDonald that he owes his own “greatest debt.”

Source References on George MacDonald (including forthcoming) HERE